Photo by Chicago Tribune

The following profile has been republished with permission from The National Registry of Exonerations.

On October 1, 2020, a special prosecutor for the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office dismissed murder and armed robbery charges against Jackie Wilson, who had been convicted twice and granted new trials in the murders of two Chicago police officers in 1982.

The arrest and prosecution of Wilson, who was 21 when he was arrested, and his brother, Andrew, 29, became one of the ugliest and sordid chapters in the history of criminal justice in Chicago.

It began on the morning of February 9, 1982, when police officers Robert O’Brien, 33, and William Fahey, 34, pulled over a rust-colored Chevrolet containing two men near the intersection of 81st and Morgan Streets.

Moments later, Fahey was dead, shot in the head with his own revolver, and O’Brien was dying after being shot several times.

Police killings trigger backlash

They were the second and third Chicago police officers to be killed in less than a week. Just four days earlier, on February 5, 1982, rookie officer James Doyle was gunned down on a Chicago Transit Authority bus. In the hours before O’Brien and Fahey were shot, they had attended Doyle’s funeral.

The killings triggered what would ever be the largest and most violent police manhunt in Chicago history. Hundreds of police officers conducted a block-by-block search for the car, kicking in doors, assaulting people and engaging in extensive physical abuse of suspects. More than 100 complaints of police misconduct were filed in just the first two days after the shootings. Most of them were lost. None of them went anywhere.

On February 14, 1982, police arrested the Wilson brothers after they found the rust-colored Chevrolet and recovered the service revolvers belonging to O’Brien and Fahey. Later that day, the department proudly announced that the Wilson brothers had confessed to the murders and implicated each other.

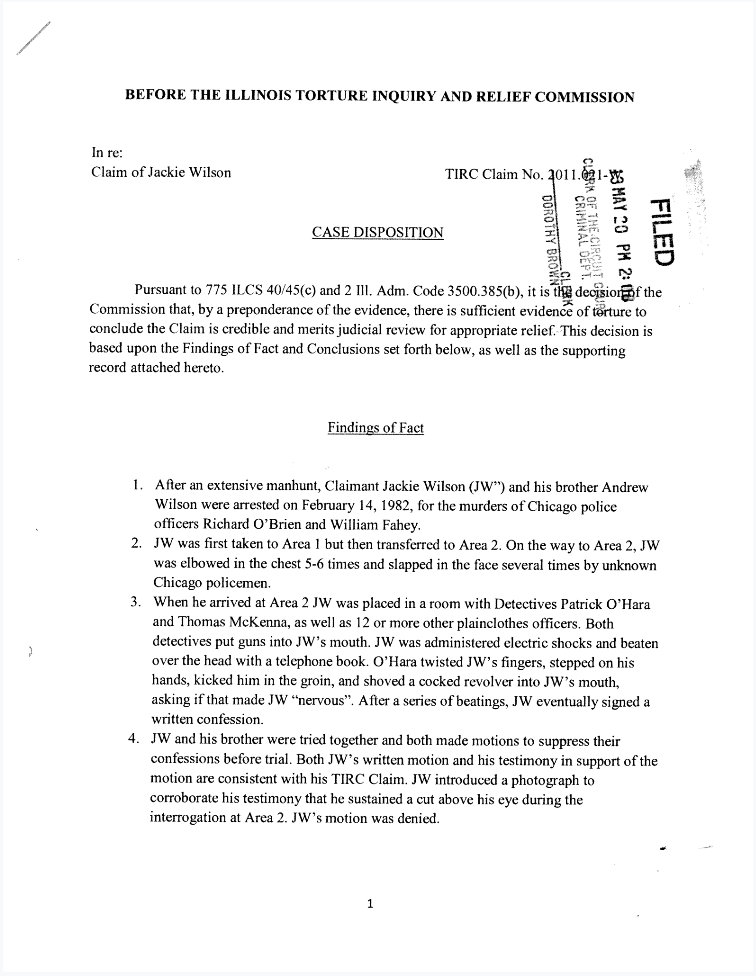

What happened between the brothers’ arrests and the announcement of their confessions in police interrogation rooms cast a shroud over the police department that resonated for decades. The Wilson brothers were tortured until they confessed. They were punched and kicked. Revolvers were stuck in their mouths and cocked. Andrew was tied to a radiator and burned. Andrew and Jackie were connected to a hand-cranked generator and given electric shocks.

The torture of the Wilson brothers, as well as scores of other men over many years, resulted in wrongful convictions of numerous defendants and ultimately, the federal perjury conviction of Lt. Jon Burge, the detective commander who oversaw the group of detectives who were notorious for their cruelty in interrogation rooms. The torture scandal cost the city of Chicago more than $100 million.

At about the same time that Fahey and O’Brien were shot, DeWayne Hardin was riding in a car on Morgan Street heading north toward 81st Street. He later said that because the street was narrowed by accumulated piles of snow, the car he was in had to pull over to allow the Chevrolet to pass. They then came upon the officers. Fahey was dead and O’Brien was struggling to get up, but would not survive. Hardin grabbed the radio in their squad car and called for help. When the first police officer arrived, he pounded on their car and yelled, “Not again!”

The Fraternal Order of Police offered a $10,000 reward for apprehension of the men in the Chevrolet. Mayor Jane Byrne announced a $50,000 reward.

On February 13, 1982, acting on information obtained through tips and by physically assaulting witnesses in police stations, detectives raided a beauty salon and recovered Fahey’s and O’Brien’s revolvers, as well as a sawed-off shotgun. The owner of the salon said that Andrew Wilson stayed there. That day, ballistics tests showed that the shotgun recovered from the beauty shop was used to commit a murder of Lloyd Wickliffe, a security guard at a McDonald’s restaurant a month before, on January 11, 1982.

Wilson brothers arrested

Andrew and Jackie Wilson were arrested on February 14 in separate locations. Police also recovered a handgun from Andrew that was identified as a gun belonging to Wickliffe. However, police did not consider Andrew Wilson a suspect in Wickliffe’s killing—by that time, two other men, Alton Logan and Edgar Hope, were charged with Wickliffe’s murder.

Hope was at Cook County Hospital being treated for gunshot wounds suffered on February 5 when he engaged in a gun battle with police attempting to arrest him. During that shooting, Hope fatally shot Officer Doyle.

Years later, prosecutors would claim that when the Wilson brothers were stopped, they were heading to Cook County Hospital where they intended to break out Hope, who was under police guard. Prosecutors made this claim even though it was undisputed that the Wilsons were driving south on Morgan Street—away from the hospital—at the time they were pulled over.

Lawyers for the Wilson brothers moved to suppress their confessions, accusing the police of torturing them. Among the defense witnesses was Dr. John Raba, a physician who examined Andrew Wilson and documented the blistering radiator burn and other injuries. Jackie testified he was chained to a wall and questioned without being given his Miranda warnings. He said he was beaten repeatedly and kicked in the groin so hard that he urinated on himself. He later added that he was shocked by the hand-cranked generator.

Detectives denied abusing the suspects and said that any injuries suffered came after they had made inculpatory statements. Judge John J. Crowley denied the defense motions to bar the use of the statements.

The Wilson brothers’ trial

In January, 1983, the brothers went to trial in Cook County Circuit Court after an all-white jury was selected. The defense asked for a mistrial accusing the prosecution of unfairly disqualifying Black jurors—Jackie and Andrew Wilson were Black; O’Brien and Fahey were white. The judge denied the motion.

The defense sought to bar the testimony of Tyrone Sims, who identified the Wilson brothers and said that Andrew was the gunman. The defense argued that Sims had been hypnotized and that his recollection had been influenced as a result. The prosecution argued that Sims had been hypnotized only in an attempt to see if he could provide a license plate number and that there would be no testimony about that. The judge denied the motion and ruled that Sims could testify to his pre-hypnotic recollection.

Sims testified that he was looking out the window of his home near the intersection when he saw the police car, with its lights flashing, pull over the Chevrolet. Sims said that the driver, whom he identified as Jackie, got out of the car and met O’Brien, who was driving the squad car, near the back of the Chevrolet. O’Brien then walked up to the open door of the Chevrolet, leaned inside, and then stood up.

At that point, the passenger in the Chevrolet, whom Sims identified as Andrew Wilson, got out. As he did, tossed a jacket back inside. The passenger in the police car—Fahey—then approached and Andrew Wilson handed him the jacket, Sims said.

Fahey searched the jacket and then took out his handcuffs. At that point, Sims said, Andrew Wilson and Fahey began to struggle. “[T]hey slipped and fell up against the trunk of the car and [Fahey] had subdued him to the point where he could try to put the handcuffs on him again,” Sims said.

Andrew Wilson “reached behind the police officer, came up with a shiny pistol placing it into the back of his head and firing—firing a shot into his head.”

Asked what happened next, Sims said. “Well, the police officer fell up against him, which, then he (Andrew Wilson) immediately pushed him off, spun around, ducked down behind the trunk of the passenger side, reaching over and firing a shot at the driver (O’Brien) of the police car.” At the time, Jackie Wilson was “still standing at the open door of the…Chevrolet on the driver’s side.”

Sims said Andrew Wilson then “jumped up on the trunk, reached over the other side and fir[ed] two more shots….He slide back off on the passenger side, picking up his belongings and going back up to the…open door of the passenger side and shouted to the driver, ‘Let’s get out of here.’”

Sims said Jackie Wilson was still standing by the open driver’s side door. That’s when Sims said he left the window to call police.

Jackie Wilson’s involvement questioned

Jackie Wilson’s attorney, Richard Kling, attempted during cross-examination to show that Jackie Wilson was not involved in the shooting. “And when [Andrew] shouted, ‘Get in the car, let’s get out of here,’ the driver, Jackie Wilson, didn’t get right into the car and get out of there, did he?”

“No,” Sims said.

“He stood there for a few seconds, didn’t he”” Kling asked.

“Yes,” Sims said.

“In fact, at the time, you thought he was in a state of shock, didn’t you?” Kling asked.

“Yes,” Sims said.

Hardin testified that he saw the Wilson brothers on either side of the rust-colored Chevrolet as he rode in a car heading north on Morgan Street. He identified Jackie Wilson as the driver and Andrew Wilson as the passenger. He also said that the car “wasn’t moving that fast. They just, you know, drove away like everything was calm. The way I noticed it is because the guy was smiling that got into the passenger side. He was smiling and that’s why I noticed it so much, it stayed in back of my mind for a long time.”

A Chicago police crime lab analyst testified that bullets recovered from the bodies were fired from Fahey’s service revolver.

The prosecution presented the statements that detectives said the brothers gave during interrogation. Jackie Wilson’s statement said that when he was unable to produce a driver’s license, O’Brien patted him down and walked to the driver’s side door of the Chevrolet. O’Brien leaned in and grabbed a .38-caliber revolver that Andrew had placed on the front seat. O’Brien then drew his own gun and told Jackie to “freeze.”

Meanwhile, according to the statement, Andrew got out of the car and tossed his jacket back inside. Fahey, who approached from the passenger side of the squad car, ordered him to take the jacket back out. Fahey found some .38-caliber bullets inside the pocket, and told Andrew he was under arrest. During a struggle, they fell against the Chevrolet. As Fahey attempted to handcuff him, Andrew Wilson took Fahey’s gun and shot him, according to the statement.

Andrew then pushed Fahey off, spun around and shot at O’Brien, who was holding Jackie Wilson at gunpoint. As O’Brien fell, Andrew ordered Jackie to “get his gun,” but when Jackie said that O’Brien was “still there…he’s up and about,” Andrew jumped onto the trunk and fired four or five more shots at O’Brien. Andrew then picked up O’Brien’s service revolver and the pistol O’Brien had grabbed from the front seat of the Chevrolet, shouted, “Let’s get out of here” and got into the passenger seat.

Jackie’s statement said he stood motionless for a few moments, but when Andrew yelled, “move, move, move!” he got in and drove away.

Appeals’ courts order new Wilson trials

On February 4, 1983, after a month-long trial, the jury convicted the brothers of murder and armed robbery. Andrew Wilson was sentenced to death. Jackie Wilson was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

In April 1987, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed Andrew Wilson’s conviction and ordered a new trial. The court ruled that the prosecution had failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that Andrew Wilson’s confession was not the result of coercion. “[T]he defendant’s statement should have been suppressed as involuntarily given,” the court ruled.

In September 1987, the Illinois Appellate Court ordered a new trial for Jackie Wilson. The court declined to suppress Jackie’s statement, but ruled that he was entitled to a separate trial from Andrew.

Andrew Wilson went to trial a second time in June 1988. The prosecutors were William Kunkle and Nick Trutenko. Sims again testified as did Hardin. Derrick Martin testified that Andrew Wilson admitted to the shooting as they rode a rapid-transit train three days after the shooting. Martin said that Andrew said he thought he was going to be arrested because the officers had found a gun under his jacket in the car. Martin’s account was similar to Sims’s account.

On June 20, 1988, Andrew Wilson was convicted a second time. This time, he was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Wilson challenges Burge in court

In February 1989, a federal civil rights trial began of a lawsuit brought by Andrew Wilson against Burge and other detectives, including John Yucaitis and Patrick O’Hara, accusing them of torturing him during his interrogation. Burge was represented by William Kunkle, the same man who prosecuted Andrew Wilson at Wilson’s second trial. Burge denied that he or his detectives engaged in torture.

In that trial, a burn expert testified that the radiator marks were not burns, but abrasions. Police claimed the radiator in the interrogation room didn’t work. All of the officers denied the allegations. On March 30, 1989, the jury found in favor of the detectives, but a mistrial was declared on the claims against Burge when the jury was unable to reach a verdict.

The retrial was conducted that summer, with Burge’s attorneys arguing that the marks on Wilson’s chest and thigh were indeed burns, but that they had been self-inflicted. Supporting that theory was Bill Coleman, an inmate at Cook County Jail. He was in the jail because he had been arrested in a Chicago suburb on charges of possession with intent to deliver more than a kilogram of cocaine. Coleman had escaped and was then captured. He was then returned to the jail where he said he met Andrew Wilson.

Coleman, a native of Liverpool, England, said Wilson told him that he had inflicted his injuries on himself and that they were not the result of torture. Lawyers for Wilson had sought to introduce the testimony of a British journalist who knew Coleman and considered him a “consummate liar,” but that testimony was excluded. Federal appeals judge Richard Posner later noted that Coleman’s claim that Wilson said his injuries were self-inflicted was “odd” because at the time of the alleged conversation, the Illinois Supreme Court had already suppressed Wilson’s confession. Posner characterized Coleman as a “peripatetic felon.”

After nine weeks, the jury found in favor of Burge. After the trial, one of the jurors, apparently believing Coleman, suggested that Andrew had inflicted the injuries on himself.

Jackie Wilson’s second trial

Meanwhile, in April 1989, Jackie Wilson went to trial a second time. The prosecutors, Nick Trutenko and William Merritt, added Coleman to the prosecution case. Coleman claimed that while in Cook County Jail, Jackie and Andrew plotted to escape with Edgar Hope so they could kill Tyrone Sims and Derrick Martin, as well as Judge Michael Getty. By that time, Hope had been convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of police officer James Doyle—the officer killed four days before Fahey and O’Brien. Hope also had been convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of McDonald’s restaurant security guard Lloyd Wickliffe. Hope’s co-defendant in that case, Alton Logan, also had been convicted. He had been sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Coleman testified that he became aware of the plot and informed authorities. Jail officials said they found a hole in the wall in one of the jail’s most secure units that had been covered with a drawing intended to mimic the wall. On the other side, guards found 100 feet of rope made from bedsheets, a hacksaw, and a homemade knife.

Wilson’s attorney, Richard Kling, attacked Coleman, who also was known as Alfred William Clarkson, as a one-time gunrunner for the Irish Republican Army who was wanted in England, Canada and three U.S. cities, primarily on fraud charges.

Coleman also had been known as Mark Krammer, Paul Roberts, Richard Hallaran, R.W. Stevenson, Doctor Roberts, W. Van der Vim, Peter Karl William, John Simmons, and William Clarkson. He had been convicted of fraud, theft, perjury, manslaughter, and blackmail.

At this trial, Sims changed his testimony regarding Jackie Wilson, saying he had a “blank look” instead of appearing in a “state of shock.” In addition, Hardin, who had testified previously that he saw only Andrew Wilson smiling in the car, now told the jury that he saw both Jackie and Andrew smiling.

Two Cook County Jail correctional officers testified that Jackie made statements while awaiting his retrial. One officer quoted Wilson as saying, “You should have killed us when (you) had the chance, killed me when you had the chance because I already killed two Chicago police officers.” The other correctional officer said Wilson threatened to kill a guard “just like I did the other two policemen, way back whenever it was.”

On May 3, 1989, Jackie Wilson was acquitted of the murder of Officer Fahey and convicted of the murder of Officer O’Brien. He was sentenced once more to life in prison without parole. After the verdict, Trutenko told the Chicago Tribune that the jurors did not believe Coleman’s testimony.

Not long after, Coleman, with the assistance of Trutenko, reached a deal on his state drug and escape charges as well as pending federal charges that allowed him to be released from custody in October 1989. He was then deported to England.

‘House of Screams’ is published

Although the torture allegations made by the Wilson brothers, as well as a few other defendants in other cases, had resulted in some media coverage, the allegations gained widespread attention in January 1990 when John Conroy, a reporter for the Chicago Reader, an alternative newspaper, published a lengthy account headlined “House of Screams.” The article detailed publicly for the first time the many allegations of torture by defendants who had been convicted. An anonymous letter to the People’s Law Office, which represented Andrew Wilson in the civil lawsuit, led them to Anthony Holmes, who had been convicted of murder and who said he had been tortured. Holmes provided a roster of men who said they had been tortured.

In September 1990, the Chicago Police Office of Professional Standards (OPS), in a report authored by OPS investigator Michael Goldston, listed the names of 50 alleged victims of torture, the names of detectives who were accused of engaging in torture or failing to take action to bring it to light. That report was not released until 1992 on the eve of a Chicago Police Board hearing on whether Burge and other detectives under his command should be disciplined. Burge had been suspended in 1991. Ultimately, in 1993, he was fired, although he was allowed to keep his pension. Detectives John Yucaitis and Patrick O’Hara, both of whom were involved in the interrogation of Andrew Wilson, were each suspended for 15 months.

That same year, in separate decisions, the convictions and sentences for Andrew and Jackson Wilson were affirmed.

In 1997, a federal judge assessed a $1.1 million judgment against the city of Chicago in favor of Andrew Wilson in his civil rights suit. The judgment was structured so that Wilson did not get any money—the largest share of it went to the People’s Law Office, which had represented Wilson in the case.

In 2002, a special prosecutor was named to investigate the growing allegations of torture. In 2003, Illinois Gov. George Ryan, citing their actual innocence, pardoned four men on death row who claimed they had been tortured: Aaron Patterson, Leroy Orange, Madison Hobley and Stanley Howard.

In 2006, after spending $17 million and reviewing nearly 150 cases, the special prosecutor reported that in three cases, including the Wilson brothers’ case, there was evidence sufficient to prove that five Burge detectives had tortured defendants. Because the statute of limitations had expired, no one was charged.

In September 2008, Alton Logan was granted a new trial and his murder charge was dismissed after evidence was revealed that Andrew Wilson—not Logan—had committed the murder of Lloyd Wickliffe at the McDonald’s along with Edgar Hope in January 1982. Logan had spent nearly 26 years in prison.

Not long after Andrew Wilson was arrested for the murders of Fahey and O’Brien, he had admitted to his lawyers that Logan was innocent in the murder of Wickliffe, and that he committed the crime. His defense lawyers were ethically bound to not reveal the admission without Wilson’s permission until Wilson died. They executed sworn statements, which were put into lockboxes. After Andrew Wilson died in prison in November 2007, the lawyers revealed his admission, leading to Logan’s exoneration.

In October 2008, Burge, who was living in Florida, was indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of obstruction of justice and perjury. U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald said Burge “lied and impeded court proceedings” in 2003 by giving false written answers to questions in a federal civil lawsuit brought by Madison Hobley claiming that Burge and other detectives engaged in torture.

In August 2009, after years of political and legal infighting, the Illinois Torture Inquiry Relief Commission was established to review claims of defendants and to make recommendations for judicial review if the claims had merit.

In 2010, Burge was convicted in U.S. District Court and sentenced to 4 ½ years in prison.

Jackie Wilson gets a new hearing

In 2015, the Torture Inquiry Relief Commission said evidence supported Jackie Wilson’s torture claim and recommended the case be opened for a hearing in Cook County Circuit Court.

In 2018, Cook County Circuit Court Judge William Hooks issued a 119-page ruling granting Jackie Wilson a new trial on the ground that he had been tortured. Hooks ordered Wilson’s statement suppressed.

“The abhorrence of basic rights of suspects by Mr. Burge and his underlings has been costly to the taxpayers, the wrongfully convicted, and worst of all, the dozens of victims and their families who have suffered untold grief —in many cases, a 30-plus year horror story,” Judge Hooks declared.

On June 22, 2018, Hooks ordered Wilson released on bond.

The prosecution appealed the ruling and in December 2019, the Illinois Appellate Court upheld the decision.

Key witness recants in new trial

As Flint Taylor and Elliot Slosar, lawyers for Wilson, prepared for the retrial, there were legal battles over whether the prosecution would be allowed to read the testimony of witnesses from Wilson’s 1989 trial. The prosecution argued that witnesses such as DeWayne Hardin and Bill Coleman were unavailable. Indeed, the prosecution said that they didn’t know whether Coleman was alive or dead.

In September 2020, Wilson went to trial for a third time, choosing to have his case decided by Judge Hooks without a jury. The testimony of Tyrone Sims was read into the record, with the prosecution reading his direct testimony from 1989 and the defense reading Sims’s cross-examination from 1983 and 1989.

The prosecution also read the direct testimony of DeWayne Hardin, whose testimony had evolved from the first trial during which he said that the passenger of the Chevrolet—Andrew Wilson—had been smiling as they drove away to testimony at Jackie Wilson’s second trial that both Andrew and Jackie had been smiling.

Hardin recanted his testimony in 2018 in a statement to Wilson’s lawyers. In that recantation, Hardin said that as the Wilson brothers drove past him, Jackie “had a scared expression on his face…he did not look happy and instead appeared to be in a state of shock.”

Hardin said that he was made to repeat a story that “the State’s Attorneys made up for me to say.” Hardin said that prior to testifying at the first trial, he told the prosecutors that “I didn’t see Jackie Wilson do anything regarding the murder…When I said that, the room exploded. People hit the table and they were agitated and upset.”

“So then they [the prosecution] threatened to violate my probation and send me to jail for five years unless I repeated their false story that Jackson Wilson was driving the brown car from the scene of the shooting while smiling,” Hardin said in the affidavit. “Jackie was sitting in the passenger seat of the car and was in a state of shock…I repeated the false story they created for me in order to save my own life.”

Relationship of jailhouse informant revealed

On September 23, 2020, after the prosecution read Hardin’s direct testimony from the 1989 trial, Wilson’s defense lawyers, rather than read the cross-examination from that trial, presented Hardin as a live witness on a video call. Hardin testified that Jackie was standing there “in a state of shock.” Asked if Jackie ever did anything to assist Andrew Wilson, Hardin said, “No, he didn’t, no.”

Hardin said that when he testified that Jackie was smiling at the 1989 trial, the testimony was false. He said he testified falsely at the behest of Nick Trutenko, the prosecutor. “I was afraid and I had to stay consistent with my testimony because I didn’t want to perjure myself,” Hardin said.

Asked if he went along with whatever Trutenko told him to say, Hardin said. “Anything he wanted me to say.”

On October 1, 2020, Slosar called Trutenko as a witness. Trutenko testified that he came back to the state’s attorney’s office in 2008 and was a supervisor in the felony review section. He admitted that in his personnel file he had been criticized by his superior for threatening witnesses. In one instance, Trutenko had been accused of threatening a woman who witnessed a double murder with contempt of court and obstruction of justice unless she testified before a grand jury. In another case, Trutenko was accused of telling a correctional officer that he “better [obscenity] testify.”

During his testimony, Trutenko was asked about Coleman. He shocked the courtroom by testifying that just days earlier he had communicated by email with Coleman—the man who the prosecutors in the Wilson case had said they believed was dead.

Trutenko also revealed that after he left the state’s attorney’s office in 1991 and went into private practice, he and Coleman became friends. In 1992, Coleman paid for Trutenko to fly to England to be the godfather of Coleman’s daughter who was being christened.

Slosar asked, “You never thought for one second to tell another person in your office that you became the godfather of (the daughter of) the jailhouse informant, is that correct?”

“No, there would be no reason to,” Trutenko said. “He wasn’t a jailhouse informant at the time I was dealing with him. I was in private practice.”

Trutenko also testified that during a virtual conversation a few days earlier with the prosecution team in the Wilson case, “Bill Coleman’s name never came up in the conversation.”

Prosecutors drop charges

Shortly after that testimony, Myles O’Rourke, one of the prosecutors, stood up. “Your Honor, based upon what I just heard, I am hereby dismissing the charges in this case.”

Hooks was caught off guard. “You’re dismissing each and every charge?”

“That is correct, your Honor,” O’Rourke said. “Your Honor, I am dismissing the entire case.”

To clarify, another attorney for the Special State’s Attorney’s Office said, “The witness [Trutenko] was asked a question and I know from my own personal knowledge that the answer was not truthful.” In fact, Coleman’s name had come up in the conversation prior to Trutenko’s testimony.

Hours later, Trutenko was fired by the State’s Attorney’s Office and was held in criminal contempt the following day. After trial, Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx declared that a potential criminal prosecution against Mr. Trutenko was referred to an outside agency.

– Written by Maurice Possley