Photo by James Gibson

The following profile has been published with permission from The National Registry of Exonerations.

On December 22, 1989, 61-year-old Lloyd Benjamin and 56-year-old Hunter Wash were fatally shot at a garage at 5757 S. May Street on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. Benjamin was an insurance agent who stopped to collect a weekly insurance premium from Wash, a mechanic who operated a car repair service.

Although police could not find anyone who saw the shooting, some witnesses said that Benjamin entered the garage around 10:30 a.m. After a brief conversation, he stepped outside. Benjamin was heard to call out to Wash and then a single gunshot was fired. Wash came out of the garage and additional shots were fired. Nothing was taken from either man.

On the evening of December 27, 1989, police received an anonymous call from a woman who said that 23-year-old James Gibson was responsible for the murders, and that he was outside his residence working to get his car running so he could leave Chicago. The caller also implicated Gibson’s brother, Harold.

Police went to the Gibson home, but no one was outside working on a car. Harold Gibson was home and police took him into custody. Later that evening, James Gibson came home and called police when he learned they were looking for him. Detectives picked him up and took him to the station.

Harold provided proof that he was elsewhere at the time of the shooting and he was released. James, however, was interrogated on and off for the next three days.

Witnesses against Gibson

On December 28, police advised Gibson he was “the focal point” of the investigation. According to police reports, Gibson said that on the morning of the shooting, he was at the home of a woman named Davis. As he was leaving, he saw a neighbor, 19-year-old Eric Johnson and Johnson’s brother who said the “insurance man” was “run over around the corner.” Gibson said he found out that both had been shot, and the word on the street was that two brothers, known as “Harp” and “Bodine,” were responsible. Gibson also said, according to the reports, that Eric Johnson had suggested robbing the insurance man a month earlier, but Gibson refused to go along.

Gibson agreed to undergo a polygraph examination that afternoon and police told him he was not being truthful when he denied involvement in the crime. During another interview, according to the reports, Gibson said that Eric Johnson and “Bodine” had approached him on the day of the shooting and asked him to go with them when they robbed the insurance man. Gibson said he refused, and when he saw Johnson later that day, Johnson said, “We got paid, from the insurance man. Keep cool.”

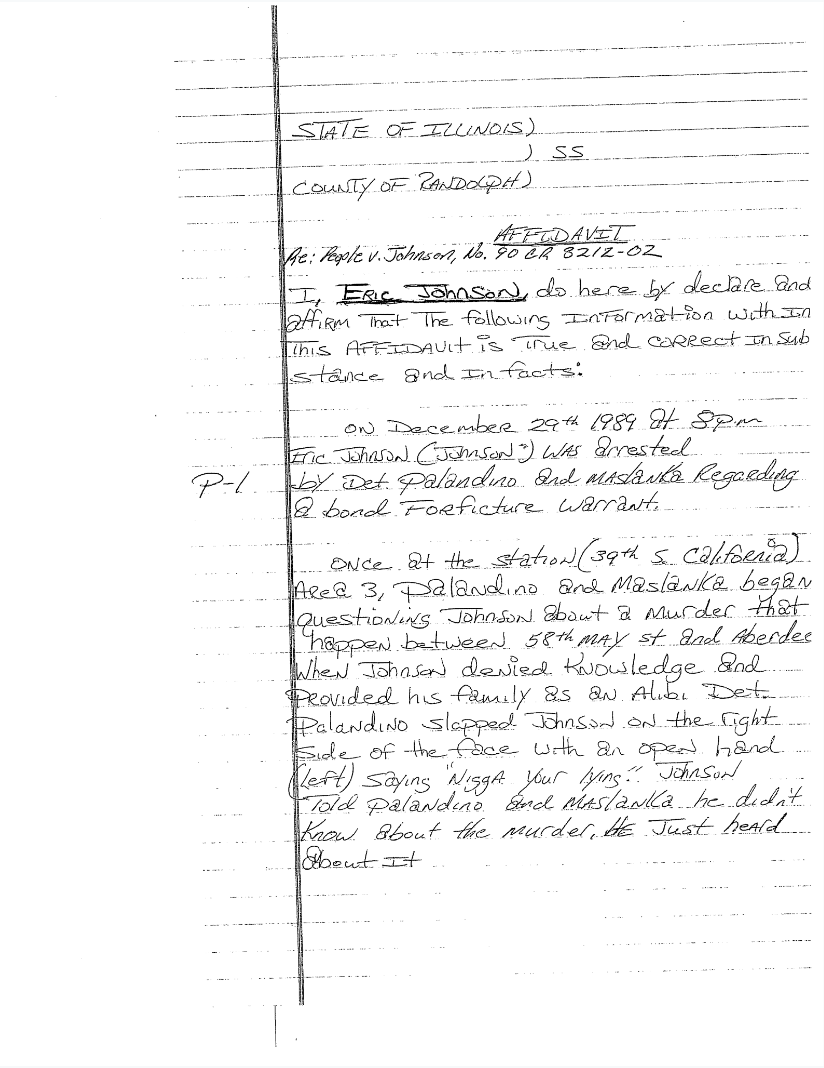

That night, detectives arrested Eric Johnson. The officers identified “Bodine” as Fernando Webb, but he was not home. The detectives then began a long series of alternating interrogations of Johnson and Gibson. Johnson said he was asleep at the time of the shooting, but that the word on the street was that Gibson had killed Benjamin and Wash, who was known as “Smiley.” Johnson said he knew Gibson by the nickname “Peter Gunn.”

Gibson, meanwhile, said he was awakened at 10:30 a.m. by a neighbor asking for a battery charger. He said he went down the street to another residence where he got the charger and brought it back for the neighbor. He said he was standing on the street with his deaf mother when Eric Johnson approached and said, “Let’s get paid from the insurance man.” Gibson said he refused and not long after, he saw Johnson and Fernando Webb head toward 58th Street. When he saw Johnson next, he was wearing different clothes and said he had gotten paid from the insurance man.

When Johnson was confronted with this statement, he said that on the day of the shooting, Gibson tried to sell him a .32-caliber nickel-plated revolver. Johnson claimed that on December 21, 1989, the day before the shooting, he saw Gibson running down the street, brandishing the gun, and trying to rob a potato chip truck. Johnson also said that several hours after Benjamin and Wash were killed, he saw Gibson sneak into the garage, apparently to hide the murder weapon.

A beaten confession

According to the reports, on the evening of December 30, 1989—24 hours into his interrogation—Gibson said that he was present at the garage when the shooting occurred. Gibson said he saw Johnson give a gun to Webb, who shot both victims.

When detectives presented this information to Johnson, he said that he saw Gibson and Webb go to the garage, and saw Gibson shoot both men as Webb acted as a lookout.

Webb was then brought in. During an interview, he said he knew nothing about the crime. He said he was out walking his dog and was returning from a dope house where he bought heroin when he saw an unidentified Black man standing by the garage door.

After conferring with a prosecutor, Gibson was released and Johnson and Webb were held for polygraph examinations.

After returning home, Gibson filed a complaint with the Chicago Police Office of Professional Standards, which investigates police misconduct. He said that detectives had slapped, punched, and kicked him. He was prompted to file the complaint by his sister, Lorraine Brown, who was home on leave from the U.S. Army. Brown had gone to the police station on December 30 to find out what was going on. She was approached by Lt. Jon Burge, the commander of the homicide unit investigating the case. Burge said that Gibson was not a suspect, and that he would be released after they finished questioning him.

Brown would later say that when Gibson came home, “he looked as though he had been in a fight” and that he said he had been beaten by police. He had urinated on the floor of the interrogation room after he was not allowed to use a bathroom.

Police charge Gibson with murder

The following day, December 31, police said Johnson showed deception “in knowledge and planning” of the shooting. When confronted with the results of the polygraph, Johnson said that Gibson came by his house just before the shooting, and offered him $50 to be a lookout while Gibson robbed the insurance man. Johnson said that when Gibson began shooting, he ran home. Johnson said Gibson later told him he shot Wash because Wash could identify him.

When detectives told Webb that Gibson said he was the gunman, Webb then said that when he was walking his dog by the garage, he saw Gibson standing nearby with a gun in his hand.

On December 31, detectives arrested Gibson on charges of first-degree murder. Johnson also was charged with the murders. Webb was not. He refused to sign a statement admitting involvement in the crime.

Internal CPD investigation

On January 2, 1990, Gibson’s public defender obtained a court order to have Gibson photographed. At the time, there were injuries noted on Gibson’s chest and buttocks.

Prior to the trial, the police department’s internal investigation of Gibson’s claims of physical abuse concluded and found no abuse. Gibson claimed that he had been punched in the ribs and neck 30 to 40 times, kicked in the groin twice, and slapped several times. Detectives gave sworn affidavits denying Gibson’s claims. The internal investigation concluded that Gibson’s claims were unfounded. The commander of the detectives, Jon Burge, said he concurred with that finding.

Gibson’s defense attorney did not file any motions to suppress his statements, so Gibson did on his own, saying later he was prompted by watching an episode of the television show Perry Mason. Gibson included a sworn statement from Johnson in which he said he also had been physically abused by the detectives until he signed a statement implicating Gibson. After Gibson’s defense attorney characterized Gibson’s statement as exculpatory, the court treated his motion as one seeking to suppress his arrest rather than his statement. The motion was denied.

Gibson went to trial on October 7, 1991 and chose to have his case decided by a judge without a jury. He was convicted the following day, largely on the testimony of a detective who said Gibson had admitted he was involved in the crime. The detective denied that Gibson was mistreated in any way.

The prosecution also presented records from the emergency room physician who examined Gibson after he was arrested and said that there was “no apparent distress…no apparent trauma” to Gibson’s body.

Two of Johnson’s sisters, Janice and Carla, testified for the prosecution that two or three days prior to the shooting, Gibson told them he was going to rob the insurance man so he could get money to fix his car. They also said that on the day of the shooting, he tried to sell a handgun to their brother, Eric.

Webb, who by then was serving a prison sentence for armed robbery, also testified. He said that he was walking his dog after buying heroin and saw Gibson near the garage holding a gun. He said that the prosecution had promised he would be released on probation after he testified.

Convicted and sentenced to life

On October 8, 1991, Gibson was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Gibson appealed, arguing that his trial defense attorney had failed to present evidence supporting his alibi—that he was retrieving a battery charger—at the time of the shooting.

In 1993, the Illinois Appellate Court upheld Gibson’s convictions. Gibson continued to file appeals, including a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus in 2005 based on his claims that he had been physically abused by the detectives working for Burge.

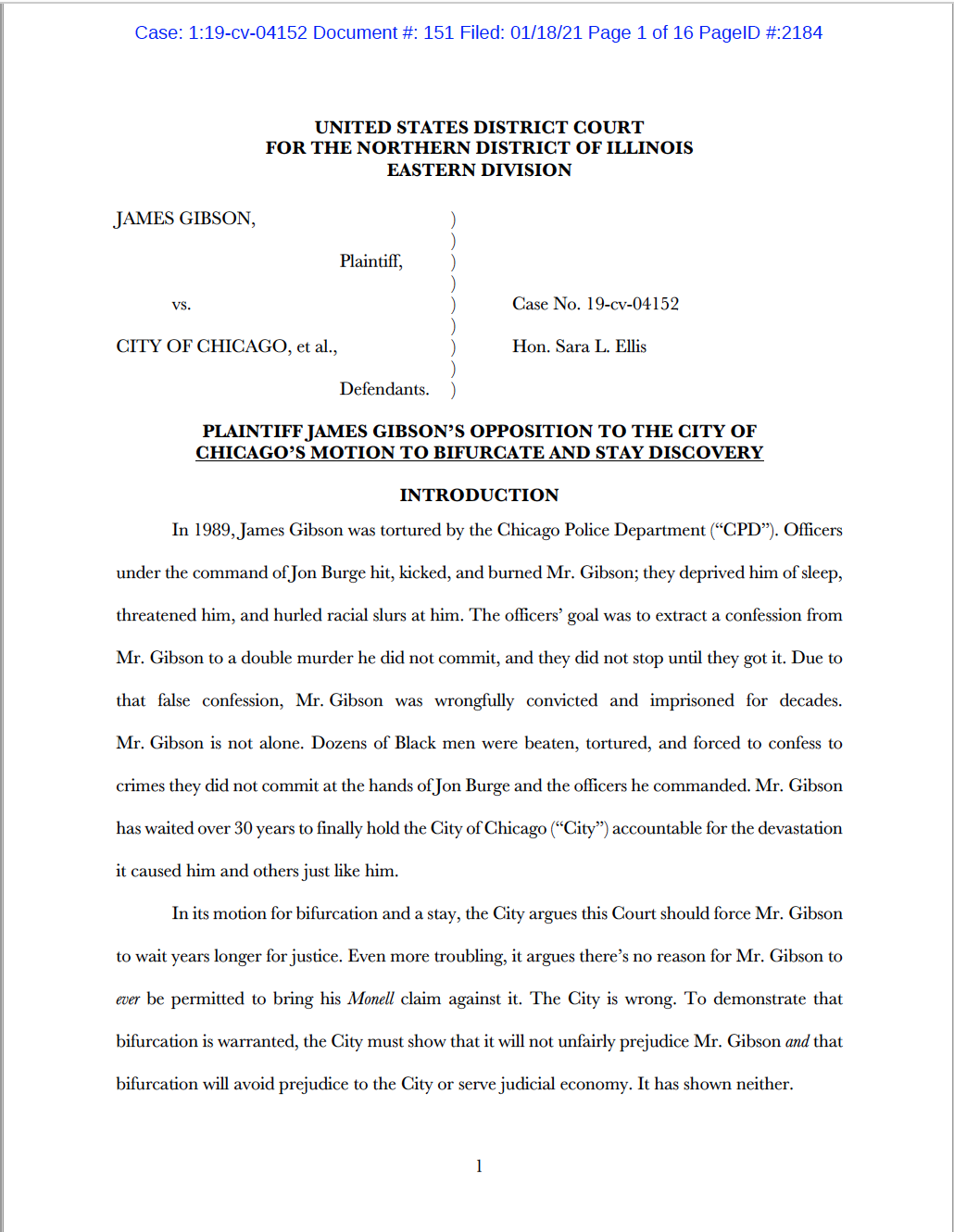

Meanwhile, Johnson had been convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison as well. After his appeal was denied, he filed a post-conviction petition in 2006 alleging that police punched and kicked him in the face and ribs until he falsely confessed and falsely implicated Gibson. That petition was denied, but while on appeal, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office agreed that Johnson had established evidence supporting his claim of being coerced through physical abuse. Back in the trial court, Johnson entered an Alford plea, which is not an admission of guilt, to one count of first-degree murder and was released from prison in 2012.

Torture allegations mount against Burge and his “Midnight Crew”

Over time, scores of other defendants raised similar claims of torture, including mock executions, electric shocks to genitals from a hand-cranked generator, and beatings. In one case, a suspect suffered burns after he was strapped naked to a radiator until he confessed.

The allegations of torture all focused on Lt. Jon Burge and detectives under his command, who became known as the “Midnight Crew” because they worked the night shift.

Burge ultimately was fired and in 2010, he was convicted in federal court of perjury for denying torture allegations during questioning in federal lawsuits brought by other torture victims. He was sentenced to 4½ years in prison.

As part of the re-examination of the torture allegations, the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission was established to investigate claims of police torture.

In 2013, Gibson filed a claim with the Torture Commission alleging that he only said that he was at the garage and saw Webb and Johnson carry out the murder to “make the beatings stop.”

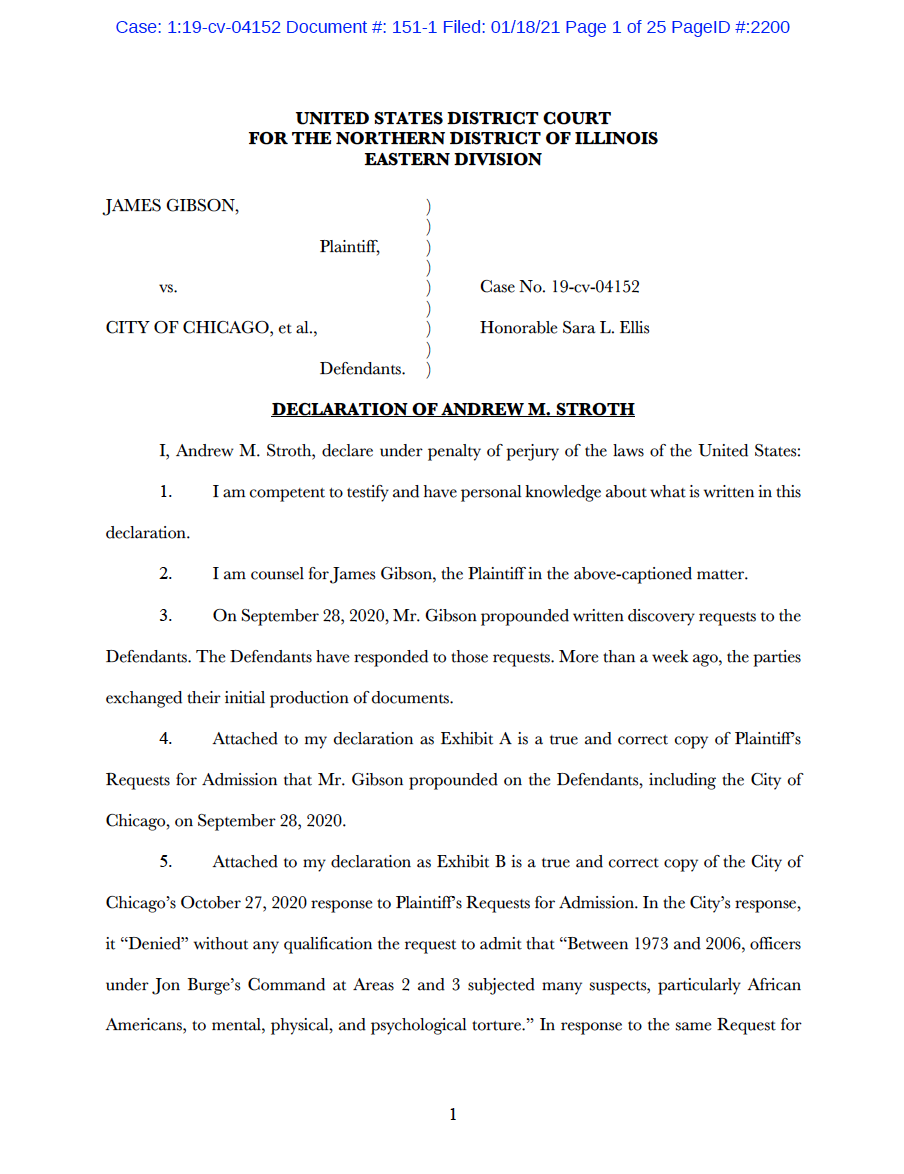

In July 2015, the Torture Commission said that despite some concerns about Gibson’s credibility based on inconsistent statements he made over the years, his core allegations remained consistent over time. In addition, the detectives involved in his case, John Paladino and Anthony Maslanka, had been identified in numerous other cases of torture. In addition, “the physical abuse described by Gibson—at a time when the widespread torture of suspects by Burge and the detectives under his command was not generally known—mirrors that described by other claimants as carried out by Mr. Burge and his subordinates,” the commission said.

Judge sides with police against Gibson

The commission said that Gibson was entitled to a hearing in Cook County Circuit Court on his claims of torture and false confession.

In 2016, prior to the hearing, Johnson’s sisters both recanted their trial testimony implicating Gibson. Both told a defense investigator for Gibson that police told them if they implicated Gibson, their brother would be released. When he was not released, the sisters said, police threatened to charge them with perjury unless they testified.

At the hearing before Cook County Circuit Court Judge Neera Walsh, Paladino and John Byrne, who was the supervising sergeant on the investigation of the murders of Wash and Benjamin, invoked their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination and refused to testify. The prosecution called other detectives who had been assigned to the investigation, but none who was involved in the interrogation. They testified they were not aware of any physical abuse in the case.

Gibson testified and admitted that he didn’t always have the facts in the proper order and that his memory was not always accurate due to the passage of time. But he recounted how Maslanka and Paladino beat and kicked him. He said Maslanka burned his tattoo off with an iron.

Judge Walsh declined to make an adverse inference based on the refusal of Paladino and Byrne to testify. She ruled there was sufficient other evidence to support the belief that no torture occurred. Judge Walsh also ruled that Gibson was not credible. She denied his petition to grant a new trial.

In 2018, the Illinois Appellate Court reversed that ruling, noting that there was no other evidence to support the detectives and the officers who testified “in truth…did not—and could not—rebut (Gibson’s) allegations in any meaningful way.” The case was remanded for Judge Walsh to reconsider her ruling after drawing an adverse inference from the refusal of Paladino and Byrne to testify. Judge Walsh reiterated her doubts about Gibson’s credibility, saying he had invented the claims to “piggyback” onto Eric Johnson’s claims, which earned Johnson a new trial in 2012. Judge Walsh dismissed the photographs of Gibson’s injuries—taken soon after his arrest—as insignificant, and suggested that they could have been caused while he was in the lockup after he was arrested or self-inflicted. She again denied the petition for a new trial.

Charges against Gibson dismissed

Gibson’s lawyers, Joel Brodsky and Ramon Moore, appealed. In March 2019, the Illinois Appellate Court vacated Gibson’s convictions and ordered a new trial. The court held that Walsh’s rejection of Gibson’s testimony was “manifestly wrong.”

The appeals court rejected Walsh’s theory of how Gibson suffered his injuries. “We will not indulge in any more speculation,” the appeals court said. “There is not a shred of evidence that (Gibson) was injured in a holding cell, at his own hands, or in any way other than one: Burge’s subordinates beat him during his interrogation.”

The appeals court also faulted Gibson’s original trial attorney for failing to raise the issue of physical abuse and coercion prior to the trial, and for claiming that Gibson’s statement that he was present when the crime occurred was actually “exculpatory.” The appeals court noted that Gibson’s statement was the “linchpin” of the prosecution’s case, and that Gibson’s trial attorney’s “incompetent advice” to not raise the physical abuse claim was “etched into the record” both pre-trial and during the trial. It was, the appeals court said, “laughably bad advice.”

On April 18, 2019, Gibson was released on bond, more than 29 years after his arrest, pending a retrial. On April 26, 2019, the prosecution dismissed the charges.

In May 2019, Gibson filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city of Chicago seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction. Gibson obtained a certificate of innocence and in August 2020 was awarded $177,071 in compensation by the state of Illinois.

– Written by Maurice Possley